Viviendas Linke Wienzeile

Linke Wienzeile- 1898 - 1899

- WAGNER, Otto

- Viena

- Austria

Otto Wagner, H. Kliczkowski, LOFT Publications. 2002. Páginas 31-33.

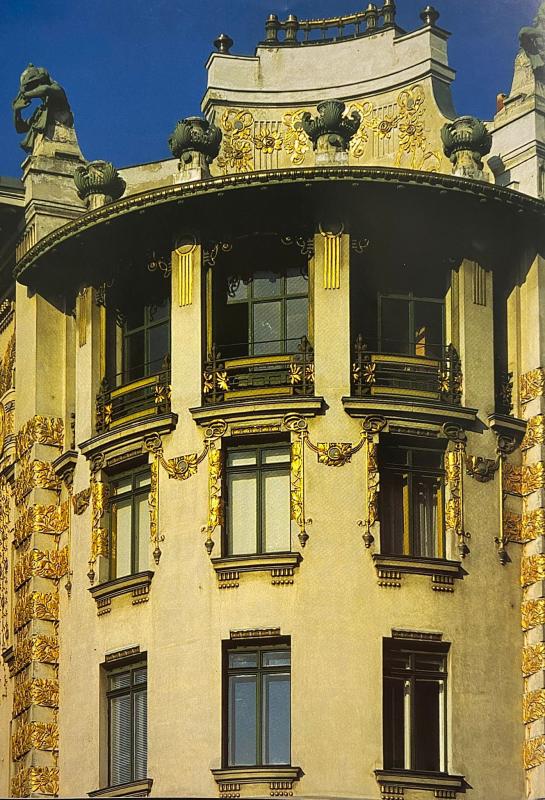

Otto Wagner proyectó esta vivienda junto a la Casa de Mayólica en la calle Linke Wienzeile, antiguamente denominada Magdalenen Strasse. Los dos edificios, contiguos, llaman la atención del paseante por sus ornamentales fachadas. Los estucos dorados que la decoran fueron encargados a Kolo Moser, artista y miembro fundador de la Sezession. La ornamentación en cascadas, los follajes y los medallones con rostros de mujer recorren el frente y contrastan con los motivos florales del bloque vecino. Más tarde ambos artistas colaborarán juntos en la iglesia de Steinhof.

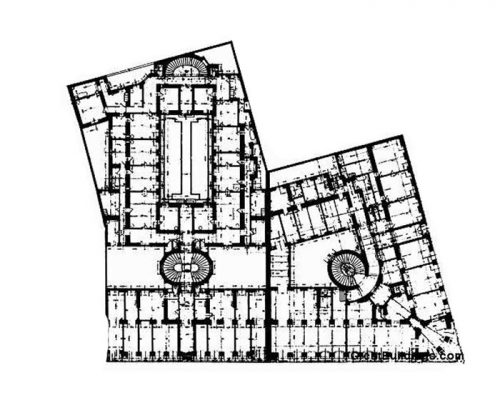

El espacio comercial acristalado de la planta baja aligera el peso del conjunto; el primer piso se une con el segundo a través de astas que se proyectan en sentido ascendente. Wagner puso especial atención en el diseño de la esquina redondeada, que presenta tres ventanas en cada piso. Coronando este chaflán se colocaron dos figuras de bronce esculpidas por Othmar Shmikowitz. Al igual que en la Casa de Mayólica, se cuidaron con esmero los detalles del interior -escalera, ascensor y barandilla- para ensalzar el estatus social de la gente que iba a habitarla. La preocupación artística de Wagner llega incluso al cartel de la puerta de entrada donde figura la dirección.

Vienna – 1900, The Architecture of Otto Wagner. Ed. Studio Editions. 1989. Páginas 108-111.

During the last decade of the nineteenth century Wagner built several apartment houses in Vienna, of which the best known is that at Linke Wienzeile 40, usually called the Majolica House. This, and its equially decorated neighbour at Linke Wienzeile 38, were conceived as a single design and provoked hostile public attention bacause of their obvious debt to the ideas of the Secession.

The majolica which gives No. 40 its name is a type of richly modelled earthenware covered in a thick glaze, which Wagner used to impose a brightly coloured overall pattern in complementary pinks, blues and greens, which combines the free, flowing curves of a floral pattern with the simple rectangular shapes of the windows. What makes this decoration innovative is not so much the colour and style used (although they were criticized in their day for their ‘wildly Secessionist element’), as the decision to keep the ornamentation almost uniformly flat and unskulptural, apart from the row of lions’ heads immediately under the eaves. The majolica has survived the rigours of the Austrian climate surprisingly well, and this house is still regarded as one of Wagner’s most famous, or notorious works.

The adjoining house on the corner of Linke Wienzeile and Kostlergasse is also decorated in highly Secessionist style, the gilded stucco and white of its facade bearing a close resemblance to the original appearance of the Secession building designed by Joseph Olbrich. Here, however, the actual form taken by the decoration seems more classical, with wreathes and rosettes repeated not only on the facade but on the metal door and in the interior hallway. The glided medallions werer designed by Kolo Moser. Above the gluttering there are four half-lenght bronze figures by Othmar Shimkowitz, which were originally gilded.

Although both these buildings were constructed in 1898-9, Wagner did not actually join the Secessionist association until October 1899. This overt commitment marked the beginning of a period of public opposition which was to last more of less until his death in 1918. Among his artistic contemporaries only Klimt provoked as much controversy. Such hostility must have seeed all the harder to bear because until this point he had been regardes as a pillar of the establishment, whose position as Professor of the School of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts assured him respect. So severe were some of the later attacks on his work and his ideas that several of the large-scale projects of his later years were shelved, including his plans for the new Academy of Fine Arts and the Kiaser Franz Josef Municipal Museum.